The Memphis & Charleston Railroad 1851-1865

The Memphis & Charleston Railroad began limited service over newly built segments of track in August of 1852. By May 1857, the line was offering regular service over the entire 272-mile route from Stevenson to Memphis. With its link in Stevenson to the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad, the Memphis & Charleston became part of the first contiguous rail route from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi River.

The Memphis & Charleston Railroad was unique in many ways. 1) It was the first railroad to offer sleeper cars. 2) It was the only railroad to run east-west in what was to become the Confederacy. 3) It made more money from its passenger service than from its freight service. 4) It was not conceived and operated as a local branch railroad, but as a long-haul route. Direct routes to the east coast and the northeast were enabled by the decision of Memphis and Charleston planners and management to adopt a standard rail gauge and to lease usage rights from adjoining rail lines. The passengers on competing rail lines, lines had that opted instead for alternate gauges and failed to negotiate usage rights with neighboring lines, were forced to deboard one train and reboard another to continue their journeys. In many cases, that distance between train terminals was spanned by steamboat or keelboat, since most early southern railroads were typically designed as nothing more than routes to the nearest river port. 5) It ran parallel a major river--the Tennessee--rather than merely feeding into the river traffic infrastructure. This parallel route was the result of the Tennessee having defeated every attempt at establishing regular freight transport over its main channel from Paducah to Knoxville. Passage was disrupted at Muscle Shoals and at a bend in the river just upstream of South Pittsburg where several geological structures--the suck, the skillet, the boiling pot--made navigation difficult under the best of conditions and even impossible much of the year. The Tennessee was essentially three different rivers.

In 1828, a small steamboat, "The Atlas," navigated the length of the river to claim a $640 prize in Knoxville, but regular and dependable commercial service for the length of the river was never realized. The river's most notable historian, Donald Davidson, noted, "...of all the great rivers east of the Mississippi, it has been least friendly to civilization. It mocked the schemes of improvers. It wore out the patience of legislators. Tawny and unsubdued, an Indian among rivers, the old Tennessee threw back man's improvements in his face and went its own way, which was not the way of the white man." (p6)

The Memphis and Charleston Railroad was a substitute for the river, not a complement to it. As a result, those towns that put their trust in the eventual ability of technology and engineering to overcome the problems of Tennessee River navigation--towns like Bellefonte--would be doomed by their decision not to embrace the new mode of transportation.

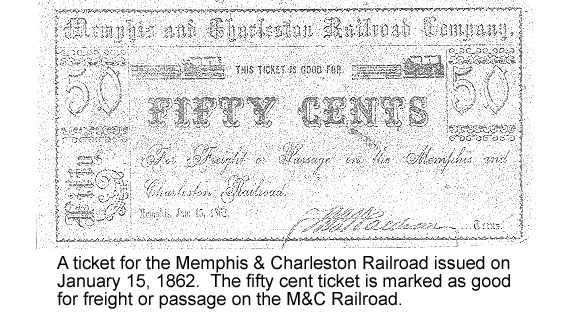

A ticket from Memphis to Chattanooga was expensive--twelve and a half dollars--but progress came at more than a monetary price: passenger cars were open to the smoke and cinders from the wood-burning firebox in the engine. The typical locomotive burned a cord of wood each 50 or 60 miles, and the principal fuel was pine, an acrid wood made more volatile by its high concentration of resin. Boiler explosions and car fires were common.

The likelihood of fire in the passenger compartments was a critical concern, but there were other hazards. Early lines were built in haste and laid on open ground without stone ballast underpinning. The railroads avoided excavation and instead bypassed obstacles by constructing sharp curves. Bridges were typically wood often without stone abutments for foundations. Braking was a slow process that required a brakeman to walk across the roofs on the individual cars to apply breaks to each car in succession. In the mid-1850's, one in every 188,000 passengers on American trains met a violent death--nine times the rate in Europe and thirty times the rate in England (page 32, Confederacy).

Among American Railroads, the Memphis and Charleston was fairly well-engineered, well-built, and boasted an impressive array of locomotives and rolling stock. In 1861, the line owned 50 locomotives, 41 passenger cars, and 13 baggage cars.

The M&C also had a good safety record. The line suffered its first passenger fatality in 1861 when a rail broke, curved up through the floor of a passenger car, and struck a passenger. With one death in 356,646 passenger boardings, the M&C was twice as safe as the typical American railroad. From 1852 until 1861, the line lost only one locomotive--the Cherokee--due to a boiller explosion.

The Memphis and Charleston Railroad enjoyed only five years of prosperity before it fell into Union hands very early in the Civil War. From the outset, the Confederate military had acknowledged the importance of the line. "The Memphis and Charleston Road is the vertebrae of the Confederacy," Robert E. Lee's advisors told him, "and must be defended at all hazards." (139) One of the earliest campaigns to seize the M&C lines was mounted by Union General William Tecumsah Sherman who in 1862 was ordered to cut the line between Corinth and Iuka, MS. Uncharacteristically, Sherman backed down from the effort, saying "I am satisfied we cannot reach the M&C Road without a considerable engagement, which is prohibited by General Halleck's instructions. (114)

However, concurrent with Sherman's failed attempts to disrupt the railroad, Confederate General Braxton Bragg wrote that the fall of the M&C was inevitable. "The disorganized and demoralized condition of our forces . . . gives me great concern. The unrestrained habits of pillage and plunder [by Confederate troops] have done much to produce this state of affairs and to reconcile the people of the country to the approach of the enemy, who certainly do them less harm than our own troops. The whole railroad system is utterly deranged and confused. Wood and water stations are abandoned; employees there and elsewhere, for want of pay, refuse to work: engineers and conductors are either worn down, or, being Northern men, abadon their positions, or manage to retard and obstruct our operations." (114-115)

Ironically, the demise of the rail was made possible by the mode of transportation it was intended to replace: the Tennessee River was easily navigable at its western end, and Northern troops used the channel to reach Corinth and Pittsburg Landing. From there, they followed retreating Confederate troops along the Memphis and Charleston tracks into north Alabama.

In April, 1862, one month after Bragg's assessment, Huntsville's railyards fell to General O.M. Mitchel. The Confederates never mounted campaigns to retake Huntsville (although Union troops abandoned the town and Confederates reoccupied it on occasion), and the South was denied the use of their crucial east-west rail route for the duration of the war.

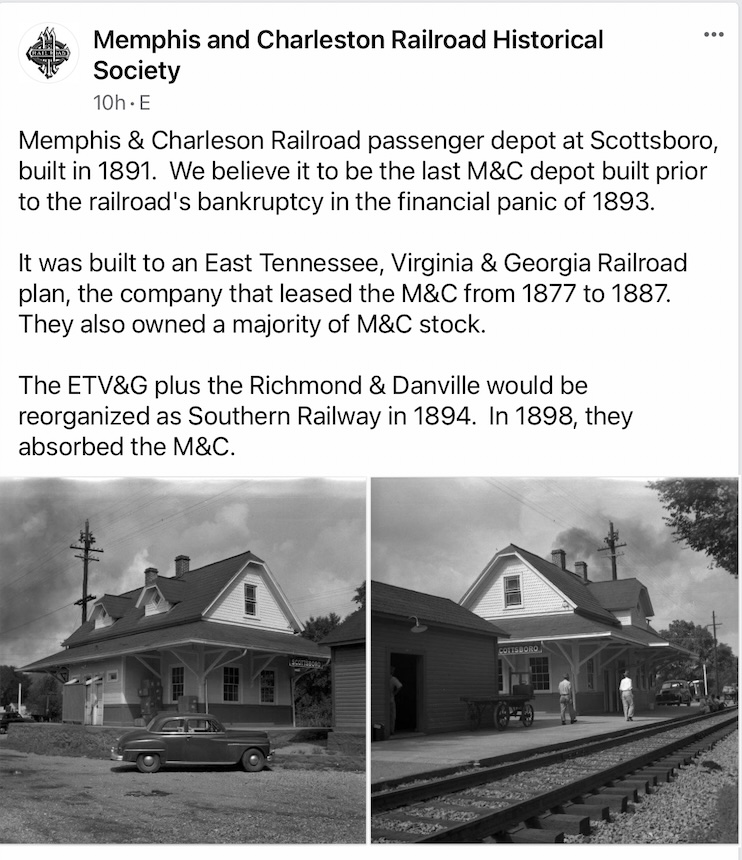

Shortly after the fall of Huntsville, General Mitchel rode through Scottsboro in the cab of a locomotive bound for Stevenson where he reported that ". . . 2,000 of the enemy fled as usual at our approach without firing a gun, leaving behind 5 locomoties and a large amount of rolling stock." (134)

Mitchel deployed troops east to Stevenson in an effort to keep the rails open to his own supply lines, but was opposed in his efforts to rebuild the Memphis & Charleston route by several Confederate Generals, including Brigadier-General Hylan Benton Lyon, who attacked union forces at the Scottsboro Depot in January, 1865.

At the war's end, the M&C rebuilt surprisingly quickly. By November of 1865, the entire road was passable with the exception of one bridge, crossing the Tennessee River at Decatur. That bridge was rebuilt and opened to traffic in July of 1866.

Financial recovery for the M&C came too slowly, however. Perhaps the final challenge came in 1887 when the US government declared the bridge over the Tennessee River in Florence to be an obstruction to navigation and ordered the bridge rebuilt at the M&C's expense. In 1894, the bankrupt M&C was reorganized under the Southern Railway System, a creation of J.P. Morgan and Company intended to consolidate several troubled lines. It wasn't until 1899 that the M&C management and operations were fully integrated into the Southern conglomerate, however. It continued to operate under the Memphis and Charleston name until 1899 when it was designated "the Memphis division" of the Southern Railroad.